Religion: Religious Leaders Pre-1900

Kong Fuzi (circa 551 BC to circa 479 BC)

Religion and Branch: Confucianism

Title: Philosopher, Teacher, Politician

Kong Fuzi, commonly Latinized as Confucius, was a philosopher, teacher, and political figure who lived during the Spring and Autumn period of ancient China. Although Confucius is not a religious figure in the traditional Western sense, his teachings, later compiled as the "Analects," became foundational for Chinese ethical and philosophical thought.

Confucius's primary concern was the cultivation of moral virtue and the establishment of social harmony. His teachings emphasized personal integrity, righteousness, proper behavior in social roles (like father-son, ruler-subject), and the importance of education.

While Confucianism is sometimes called a religion, it's more accurately described as a moral and philosophical worldview. It doesn't involve the worship of deities in the way many religions do, nor does it delve deeply into metaphysics or the afterlife.

During the Han Dynasty, Confucianism was adopted as the official state ideology. This set the stage for the incorporation of Confucian thought into Chinese governance, education, and society for the next two millennia.

Confucius emphasized the importance of ritual in creating social harmony and reinforcing social roles. This encompassed not just grand state ceremonies but everyday manners and behaviors.

After his death, Confucius's teachings gained increasing prominence. Over time, he came to be revered as the ultimate sage and teacher. Many temples were dedicated to him throughout China, and an official cult of Confucius was established, wherein he was venerated with regular ceremonies.

Confucianism has seen revivals and declines over the centuries. While it faced criticism and suppression during certain eras, such as the early Qing Dynasty and Cultural Revolution, its influence on Chinese thought and values remains undeniable.

Confucius's legacy in China is profound. Although he is not a "religious" figure in the Western sense, his teachings shaped the ethical, philosophical, and cultural fabric of Chinese society for centuries and continue to be influential today.

Laozi (6th Century BC to 5th Century BC)

Religion and Branch: Taoism

Title: Philosopher

Laozi, often rendered as Lao-tzu, is a semi-legendary figure traditionally regarded as the founder of Taoism, one of China's major philosophical and religious traditions.

Laozi is attributed as the author of Daodejing (or Tao Te Ching), a foundational text of Taoist philosophy. This short yet profound work presents the principles of the Dao (often translated as "the Way"), which represents the fundamental, natural order of the universe, and the virtue (De) of living in harmony with it. Laozi's teachings emphasize simplicity, spontaneity, and non-contention. He advocated for a return to a simple and natural way of life, emphasizing harmony with the Dao.

While the "Daodejing" is primarily philosophical, Laozi's figure and teachings became central to the religious manifestations of Taoism that developed later. In religious Taoism, Laozi is venerated as a deity and is sometimes regarded as an incarnation of the Dao itself.

Laozi's thought has deeply influenced Chinese culture, permeating various fields from philosophy and ethics to arts and governance. Taoist principles advocate harmony with nature, and this has influenced Chinese art, medicine, and even martial arts.

The historical existence of Laozi is a matter of debate among scholars. Some believe he was a real historical figure who lived during the 6th century BC, while others argue that he might be a legendary composite of multiple scholars or that the "Daodejing" was the work of several authors over time.

here are legends that Laozi met Confucius, another towering figure in Chinese philosophy, although historical authenticity for such encounters is debatable. Still, these tales illustrate the intertwined nature of Taoist and Confucian thought in China's cultural history.

Laozi, whether as a historical figure or a symbolic representation, stands central to the Taoist tradition, which has played a foundational role in shaping Chinese spiritual, philosophical, and cultural landscapes for millennia.

Zhang Daoling (34–156)

Religion and Branch: Taoism

Title: Celestial Master, Founder of Way of the Celestial Masters

Zhang Daoling, also known as Zhang Tianshi or Celestial Master Zhang, is a pivotal figure in the history of Taoism, a major religious and philosophical tradition in China.

While Taoism as a philosophy dates back to texts such as Daodejing and Zhuangzi, Daoling is credited with founding the first organized religious form of Taoism known as the Way of the Celestial Masters or Tianshi Dao. It became the foundation for several other Taoist sects and schools that emerged later. Zhang's descendants, particularly in the early years, continued to play a significant role in leading the movement.

According to Taoist tradition, around 142 AD, Daoling received a revelation from Laozi, the semi-mythical figure considered the founder of Taoist philosophy. Laozi reportedly appointed Zhang as celestial master and instructed him to establish a new religious movement to cleanse humanity of sins and heal the world. The celestial masters faced various challenges, including state persecutions, but managed to survive and adapt. Over time, they moved to other parts of China and continued to influence the evolution of Taoist religious practices.

Daoling established a theocratic Taoist community in what is now Sichuan province. This community had its own religious structure, rituals, and practices. They followed a moral code based on repentance and redemption, and they also used talismans and rituals for healing.

Daoling played a foundational role in transforming Taoism from a primarily philosophical tradition to an organized religion with its own distinct practices, rituals, and institutions. He is venerated as a saintly figure in Taoist temples, especially among sects tracing their lineage to the Celestial Masters. His teachings and practices remain integral to Taoist religious life in China.

Lushan Huiyuan (334–416)

Religion and Branch: Buddhism

Title: Monk, Founder of Donglin Temple

Lushan Huiyuan (also simply known as Huiyuan) was a prominent Buddhist monk during the Eastern Jin dynasty and is particularly remembered for his contributions to the development and spread of Buddhism in China.

Huiyuan founded the famous Donglin Temple on Mount Lu in Jiangxi province. It became a significant center of Buddhist learning, attracting scholars and monks from various regions.

Huiyuan is credited as one of the early Chinese proponents of Pure Land Buddhism. He emphasized the practice of reciting the Buddha Amitabha's name to be reborn in the Western Pure Land. His teachings and writings helped pave the way for the later development and popularity of the Pure Land school in China.

Huiyuan argued that Buddhist monks, due to their renunciation of the world, should not be compelled to participate in state rituals or pay homage to the emperor. This stance initiated a long-standing debate on the relationship between the monastic community and the state in Chinese Buddhism.

Huiyuan engaged in dialogues and interactions with Taoist and Confucian scholars. He was known for his ecumenical approach, seeking common ground between different religious and philosophical traditions. Huiyuan also wrote extensively on various Buddhist topics, including meditation, Pure Land practices, and the nature of enlightenment. His writings have been influential in shaping the course of Chinese Buddhist thought.

Huiyuan also initiated religious ceremonies and community activities that would become standard in Chinese Buddhism. He was deeply respected by both the monastic community and laypeople.

Huiyuan was a pioneering figure in the history of Chinese Buddhism, playing a crucial role in its doctrinal development and the adaptation of Buddhist practices to the Chinese cultural context.

Padmasambhāva (circa 8th and 9th Centuries)

Religion: Buddhism

Title: Guru

Padmasambhāva, also known as Guru Rinpoche, is a seminal figure in the history of Tibetan Buddhism. Credited with introducing Tantric Buddhism to Tibet in the 8th century, he was invited to the region by Tibetan King Trisong Detsen to help establish Buddhism in the region.

Tibetan lore recounts that Padmasambhāva subdued local deities and spirits, converting them to Buddhism. This helped in integrating the indigenous Bon religion with incoming Buddhist traditions.

With King Trisong Detsen and the Buddhist abbot Shantarakshita, Padmasambhāva founded Samye, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet, marking a significant turning point in Tibetan religious history.

Padmasambhāva is said to have hidden numerous terma (spiritual treasures) throughout Tibet, Bhutan, and the Himalayas. These are meant to be discovered by tertons (treasure finders) at appropriate times in the future, providing teachings suited for those specific times.

Padmasambhāva is believed to reside in the Copper-Colored Mountain, a pure land where he continues to teach to this day. He's considered an eternal figure who can be invoked and called upon for blessings, guidance, and protection.

Padmasambhāva's teachings and influence are foundational for the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, the oldest of the four major traditions. His impact, however, extends across all Tibetan Buddhist schools, and his veneration as Guru Rinpoche is widespread.

Padmasambhāva was instrumental in firmly establishing Buddhism in Tibet, blending it with local traditions and ensuring its continued relevance through the terma tradition. His legacy persists as a central figure of devotion and reverence in Tibetan Buddhism.

Guifeng Zongmi (780-841)

Religion and Branch: Buddhism

Title: Monk, Scholar, Writer

Guifeng Zongmi was an influential figure in the history of Chinese Buddhism, particularly within the Chan (Zen) and Huayan traditions. His writings and commentaries have left a significant impact on the doctrinal development of these schools.

Zongmi was unique in that he was both a patriarch of the Chan (Zen) school and a scholar of the Huayan school. This dual affiliation allowed him to integrate the meditative practices of Chan with the doctrinal depth of Huayan, providing a rich synthesis of Buddhist thought.

Zongmi is perhaps best known for his efforts to classify various Buddhist teachings based on their doctrinal depth and completeness. His classifications aimed to demonstrate the superiority of the Chan school's teachings, while also recognizing the value and legitimacy of other Buddhist traditions.

Zongmi was a prolific writer, producing numerous commentaries on foundational Buddhist texts, as well as original works elucidating Chan and Huayan teachings. His writings have been crucial in shaping the doctrinal understanding of these schools in subsequent generations.

While the Chan school is often associated with the idea of sudden enlightenment, Zongmi offered a more nuanced perspective. He argued for a balance between sudden awakening and gradual cultivation, emphasizing the importance of both insight and ethical practice in the path to enlightenment.

Zongmi's efforts to systematize and classify Buddhist teachings have been influential not only in China but also in the broader East Asian Buddhist context. His integration of Chan and Huayan thought has been a topic of study and debate for scholars and practitioners alike.

Zongmi was a central figure in Chinese Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty, providing doctrinal clarity and synthesis at a time when various Buddhist schools were competing for imperial favor and popular support. His writings and teachings have had a lasting impact on the development of both Chan and Huayan Buddhism in East Asia.

Chen Tuan (871-989)

Religion and Branch: Taoism

Title: Taoist Master, Scholar

Chen Tuan (also known as Chen Xi Yi) was a renowned Taoist sage and hermit of the late Tang and early Song dynasties. His contributions to Taoism, Chinese martial arts, and internal alchemy have left an indelible mark on Chinese religious and cultural traditions.

Tuan is particularly remembered for his contributions to Taoist thought and practice. He was deeply associated with the Quanzhen School of Taoism, even though the school formally emerged after his time.

As a Taoist hermit, Chen Tuan delved deep into the practices of internal alchemy (Neidan) and meditation. These practices aimed to cultivate vital energy (Qi) and achieve spiritual enlightenment and immortality.

Tuan is credited with creating a specific arrangement of the eight trigrams, often associated with the legendary figure Fuxi. This arrangement has been influential in Taoist cosmology and Chinese divinatory practices. He is also linked to the development of certain Chinese martial arts and health exercises, including a form of Tai Chi.

Tuan is often associated with Hua Shan, one of China's sacred mountains, where he is believed to have lived in seclusion for several years. Today, his legacy is still remembered and revered on the mountain, which remains a popular pilgrimage site for Taoists and tourists alike.

Tuan was a pivotal figure in the evolution of Taoism during the transition from the Tang to the Song dynasty. His emphasis on meditation, internal alchemy, and harmonization with the Dao has greatly influenced Taoist practices, martial arts, and the broader religious landscape of China.

Wang Chongyang (1113-1170)

Religion and Branch: Taoism

Title: Philosopher, Poet, Founder of Quanzhen School of Taoism

Wang Chongyang was a prominent figure in the history of Chinese Taoism. He was the founder of the Quanzhen ("Complete Perfection" or "All True") School of Taoism, which merged Taoist principles with elements from Confucianism and Buddhism.

Chongyang's establishment of the Quanzhen School was revolutionary for Taoism. This school emphasized monasticism, moral cultivation, meditation, and alchemy, aiming for a synthesis of Taoist inner alchemical practices with the ethical teachings of Confucianism and the spiritual practices of Buddhism.

Unlike many earlier Taoist traditions that were more lay-focused, Quanzhen Taoism emphasized monastic life. Wang himself led an ascetic life, and he encouraged his followers to do the same. This emphasis on monasticism brought Quanzhen Taoism closer in practice to some forms of Buddhism.

Chongyang's teachings were propagated by his seven primary disciples, who are often referred to as the Seven Masters of Quanzhen. These disciples played vital roles in spreading and institutionalizing the Quanzhen tradition after Wang's death.

Quanzhen Taoism became one of the dominant forms of Taoism in the subsequent Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. The school's emphasis on moral rectitude and spiritual practice made it highly influential, and it remains a significant tradition within Taoism to this day.

Chongyang's life and teachings also influenced Chinese literature, notably in works such as The Journey to the West, where Taoist principles and figures inspired by the Quanzhen tradition appear. His impact on religion in China was profound, reshaping Taoism's landscape through the establishment and spread of the Quanzhen School. His efforts to integrate Taoist practices with the moral teachings of Confucianism and spiritual practices of Buddhism created a unique religious tradition that has persisted for centuries.

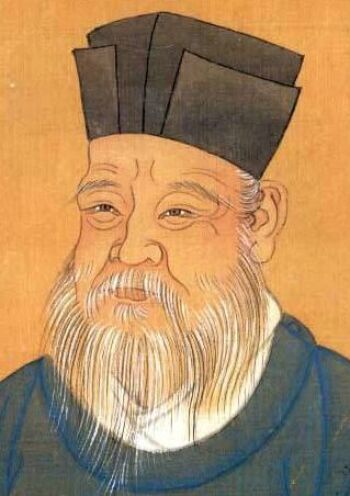

Zhu Xi (1130-1200)

Religion and Branch: Neo-Confucianism

Title: Philosopher, Historian, Politican, Poet

Zhu Xi is a towering figure in the intellectual history of China, renowned primarily for his contributions to Confucian philosophy rather than religion in the conventional sense. Nevertheless, his interpretations had profound spiritual and moral implications.

Xi is often referred to as the leading figure of Neo-Confucianism (often known in Chinese as Daoxue or "Teaching of the Way"). This movement sought to revitalize Confucian thought by integrating insights from Buddhism and Taoism.

Xi emphasized four books (Analects, Mencius, Great Learning, and Doctrine of the Mean) as foundational texts for Confucian study. His commentaries on these works became the standard readings, and they profoundly influenced the imperial examination system and education in China for centuries.

Xi introduced a metaphysical framework involving the concepts of "li" (principle or order) and "qi" (material force). He posited that everything in existence is composed of both "li" and "qi", with "li" being the eternal, unchanging principle and "qi" being the dynamic, changing force. He emphasized the importance of self-cultivation and introspection. Drawing from the Confucian classics, Zhu Xi believed that understanding the universal principles ("li") could guide one's moral actions and lead to the betterment of society.

Xi also underscored the importance of ritual in daily life, not just as mere formalities but as expressions of one's internal moral state and as tools for moral cultivation. His philosophical and moral teachings had a lasting impact on East Asian Confucian traditions, not just in China but also in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. His interpretation of Confucianism remained dominant in China's educational system until the end of the imperial era in the early 20th century.

Xi operated within the Confucian framework, which is often characterized as a philosophy or ethical system rather than a religion in the Western sense, his influence on the moral and spiritual dimensions of Chinese society is undeniable. He played a pivotal role in reshaping Confucian thought, making it more systematic and deeply philosophical.

Qiu Chuji (1148-1227)

Religion and Branch: Taoism

Title: Taoist Master

Qiu Chuji, also known by his Taoist name Changchun Zhenren, was a prominent Taoist figure during the Jin and early Yuan dynasties in China. He is particularly noted for his leadership in the Quanzhen School of Taoism and his interactions with the Mongol leader Genghis Khan.

Chuji was one of the leading disciples of Wang Chongyang, founder of Quanzhen School of Taoism. After Chongyang's death, Qiu played a pivotal role in propagating and institutionalizing the Quanzhen tradition, helping it gain widespread acceptance and prominence. Chuji established several Taoist monasteries and communities, further strengthening the monastic tradition within the Quanzhen School. His efforts helped standardize practices and teachings, ensuring the longevity of the school.

One of the most famous episodes in Chuji's life is his journey to Central Asia to meet Genghis Khan. The Mongol leader had sent an invitation to Chuji, curious about Taoism and the pursuit of immortality. Their meeting in Afghanistan is legendary, and Chuji is said to have impressed Khan with his wisdom and teachings, emphasizing the impermanence of life and the importance of moral virtues.

Due to Chuji's influence, Khan issued decrees granting certain privileges and protections to the Quanzhen Taoists. This patronage provided a favorable environment for the spread and practice of Taoism in areas under Mongol control.

Chuji was a key figure in the development and spread of the Quanzhen School of Taoism during a transformative period in Chinese history. His interactions with Genghis Khan and his efforts to establish Taoist institutions have left a lasting mark on the religious landscape of China. Chuji's leadership solidified the Quanzhen School's status as one of the leading Taoist traditions in China. The monasteries and institutions he established continued to flourish long after his death, and his teachings and writings remain influential within Taoism.

Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani (circa 1312-1384)

Religion and Branch: Islam (Sufism)

Title: Sufi Saint, Islamic Scholar, Missionary

Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, also known as Shah Hamadan, is a revered Islamic scholar and Sufi saint. Particularly famous for his role in spreading Islam to the Kashmir Valley.

Born in Hamadan, Persia (modern-day Iran), Hamadani belonged to a noble and learned family. His lineage is traced back to the Prophet Muhammad, making him a Sayyid (a title given to the descendants of the Prophet).

As a prominent Sufi, Hamadani's teachings focused on love, devotion, and the internal aspects of Islam. He emphasized the esoteric dimensions of the faith and advocated for a personal and direct experience of God through mysticism.

While Islam had made inroads into the Kashmir Valley before his arrival, Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani is often credited with consolidating its presence there. He, along with his 700 followers (often referred to as "the 700 Sayyids"), made a significant impact on the religious landscape of Kashmir. His peaceful means of propagation, combined with his spiritual teachings, attracted many to Islam.

Apart from his missionary work, he was an accomplished writer and scholar. His most famous work is , a treatise that deals with various subjects including theology, governance, ethics, and more. His writings played a crucial role in the intellectual and spiritual development of Muslims in the region.

Beyond his strictly religious influence, Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani also left a profound cultural and socio-economic mark on Kashmir. He introduced Persian arts, crafts, and traditions to the region. For instance, the art of making Pashmina shawls, which is a significant craft in Kashmir, is said to have been introduced by him.

Hamadani is remembered and revered not only as a spiritual leader but also as a social reformer in Kashmir. He played a critical role in shaping the religious and cultural landscape of the region. Many mosques and shrines dedicated to him can be found in Kashmir, underscoring his lasting legacy.

Hamadani's impact on the religious and cultural life of Kashmir was profound. Through his teachings, writings, and personal example, he left an indelible mark on the region, the effects of which can still be seen today.

Wang Yangming (1472-1529)

Religion and Branch: Neo-Confucianism

Title: Scholar, Philosopher, Politician

Wang Yangming, also known as Wang Shouren, was a prominent Confucian scholar, philosopher, and official of the Ming Dynasty. His teachings, often referred to as the School of Mind (or Lu-Wang School after its founders Lu Jiuyuan and Yangming), contrasted with the orthodox Neo-Confucianism of Zhu Xi.

Yangming's most famous doctrine is Unity of Knowledge and Action. He believed that knowledge and action were indivisible; to truly know something is to act upon it. This was in opposition to the prevailing view that knowledge came before moral action.

Yangming asserted that every individual has an innate moral knowledge, a conscience of sorts, which he referred to as "liangzhi" (良知). This intuitive moral sense could guide a person to righteousness if it were genuinely and introspectively consulted.

While Zhu Xi emphasized the study of "li" (principle) in the external world, Wang Yangming believed that true understanding comes from introspection. He argued that moral principles are inherent in our minds, and excessive focus on external study could distract from genuine moral cultivation.

For Yangming, moral cultivation was a matter of cultivating one's mind and heart. He believed that each person had the capacity for moral perfection by genuinely understanding and acting on their innate knowledge.

Yangming's teachings were particularly influential in Japan, where they played a role in the development of various samurai philosophies and the modernizing movements of the Meiji period. In China, his thoughts became part of the broader fabric of Confucian thought and inspired various intellectual movements in the late Ming and Qing dynasties.

While Confucianism led by thinkers such as Yangming is more a philosophy or way of life than a religion in the Western sense, its profound moral and spiritual teachings influenced the ethical fabric of society. Yangming's emphasis on introspection and innate moral knowledge shifted the focus of Confucian practice inward, giving individuals a more direct role in their moral cultivation.

Matteo Ricci (1552-1610)

Religion and Branch: Christianity (Catholicism)

Title: Jesuit Priest, Missionary

Matteo Ricci was an Italian Jesuit priest who played a seminal role in introducing Catholicism to China during the late Ming Dynasty. His approach to mission work and his profound respect for Chinese culture and learning make him a unique figure in the history of Christian missions.

Unlike many missionaries of his time, Ricci adopted Chinese customs, language, and dress. This strategy, known as accommodation, was meant to present Christianity in a way that would be culturally relatable to the Chinese.

Ricci was a learned man, proficient in subjects like mathematics and astronomy. He engaged with Chinese scholars, contributing to their knowledge in these fields while also discussing philosophy and religion.

Ricci authored several books in Chinese, explaining Christian doctrine and European science. His most famous work, The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, sought to present Christianity in terms that Confucian scholars would appreciate.

Ricci introduced a detailed map of the world to China. This map combined European knowledge of geography with Chinese cartographic traditions and was well-received by Chinese scholars.

With his deep respect for Chinese culture and his scholarly approach, Ricci was able to establish a Jesuit presence in Beijing, the imperial capital. This was a significant accomplishment, opening doors for further interactions between China and the West.

Ricci believed that Confucian rites were more cultural than religious and that they could be compatible with Christian beliefs. This laid the foundation for the later Chinese Rites controversy, a significant debate within the Catholic Church regarding the adaptation of local customs in missionary activities.

Ricci stands out as a pioneering missionary who approached evangelization in China with cultural sensitivity and intellectual engagement. His efforts laid the foundation for further Catholic missionary activities in China, and his legacy in Sino-European relations and intercultural dialogue remains influential to this day.

Ma Zhu (1640-1710)

Religion and Branch: Islam

Title: Islamic Scholar

Ma Zhu, also known as Ma Dexin, was a prominent Chinese Muslim scholar during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.

Zhu was renowned for his expertise in Islamic jurisprudence, theology, and Sufism. He was deeply rooted in the Hanafi school of thought, one of the four major Sunni Islamic schools of jurisprudence.

Zhu is noted for his efforts to harmonize Confucian teachings with Islamic principles. He believed that there was compatibility between the moral and ethical teachings of Confucianism and Islam, and he sought to bridge understandings between the two traditions.

Zhu authored numerous works on Islam, addressing a wide range of topics from theology to rituals and practices. His writings served as valuable resources for Chinese Muslims, aiming to deepen their understanding of Islam in the context of Chinese culture.

Zhu played a crucial role in the intellectual and religious life of the Hui Muslim community in China. His efforts in integrating Confucian and Islamic thought left a lasting impact and set a precedent for future Chinese Muslim scholars.

Jean-Baptiste Régis (1663/1664-1738)

Religion and Branch: Christianity (Catholicism)

Title: Missionary

Jean-Baptiste Régis was a French Jesuit missionary who played a significant role in the Christian missionary activities in China during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. He was sent to China around the 1690s as part of the Jesuit China missions.

Like many of his Jesuit contemporaries in China, Régis was not only involved in religious evangelism but also in scientific and intellectual exchanges. He, along with fellow Jesuits, was involved in revising the Chinese calendar, a project endorsed by the Qing Dynasty emperors because of the Jesuits' expertise in astronomy.

Régis, in collaboration with other Jesuits, was engaged in cartographic endeavors. He contributed to a significant project to map the Chinese empire, a task that had the patronage of the Kangxi Emperor. This project produced a large and detailed atlas of China, which was an impressive achievement of its time.

The Jesuits, including Régis, often interacted with the Chinese scholarly elite and the imperial court. Their approach was one of accommodation, wherein they sought to find commonalities between Christian and Confucian teachings, though this approach sometimes led to controversies within the Catholic Church.

Régis, through his work in the realms of religion, science, and cartography, contributed to the rich tapestry of cultural and intellectual exchanges between China and the West during the late Ming and early Qing periods. He was a notable figure in the Jesuit mission in China, contributing to both the religious evangelization and the scientific and intellectual exchanges between China and the West.

Hong Xiuquan (1814-1864)

Religion and Branch: Mix of Protestant Christianity and Chinese Folk Religion

Title: Religious Leader, Revolutionary, Leader of God Worshipping Society Movement

Hong Xiuquan is a notable figure in Chinese history, primarily due to his role as the leader of the Taiping Rebellion, one of the deadliest conflicts in history. His religious beliefs and visions were central to the formation and direction of the rebellion.

After failing the imperial examinations multiple times, Xiuquan experienced a series of visions. Following contact with Christian tracts, he reinterpreted these visions and came to believe that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ, sent to purge China of the "devils," which he associated with the ruling Qing Dynasty and traditional Chinese deities.

Using his religious teachings and vision as a basis, Xiuquan established the God Worshipping Society, a religious movement that drew on his own unique interpretation of Protestant Christianity and combined it with Chinese folk religion. Later in 1851, it was renamed Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Taking the title of heavenly king, Xiuquan aimed to replace Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism with his interpretation of Christianity.

The Taiping Rebellion, fueled by Xiuquan's religious movement, spread across much of southern and central China and lasted for 14 years (1850-1864). The conflict led to the deaths of millions, with estimates ranging from 20 million to 30 million people. Despite achieving significant successes in the early and middle stages of the rebellion, the Taiping forces were eventually defeated by the Qing Dynasty with the assistance of foreign powers. The fall of Nanjing in 1864 marked the end of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Xiuquan died in June of that year, shortly before the fall of the city, under unclear circumstances.

Xiuquan's religious movement left a profound impact on Chinese history, providing the foundation for the massive Taiping Rebellion against the Qing Dynasty. The rebellion significantly weakened the dynasty, paving the way for future reform movements and ultimately the 1911 revolution that ended imperial rule. His challenge to traditional Chinese religion and the Confucian order also had lasting implications for China's religious landscape.

Xiuquan's religious beliefs were central to the formation, goals, and actions of the Taiping Rebellion, a major event in 19th-century China. His unique interpretation of Christianity and his vision of himself as a messianic figure shaped one of the most significant socio-political-religious movements in Chinese history.

Yang Wenhui (1837-1911)

Religion and Branch: Buddhism

Title: Scholar, Reformist, Founder of Buddhist Research Society

Yang Wenhui was a significant figure in the history of Chinese Buddhism during the late Qing Dynasty. He is best known for his pivotal role in the modern revival of Buddhism in China, particularly through his efforts to publish and disseminate Buddhist texts.

At a time when Buddhism in China was seen as declining and was often criticized by reformists and modernists, Wenhui became a leading figure in the movement to revive and reform Chinese Buddhism. His efforts laid the groundwork for the modern Buddhist revival in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

One of Wenhui's most notable contributions was his emphasis on printing and disseminating Buddhist scriptures and literature. In 1866, he established the Jinling Sutra Printing Press in Nanjing, which became a crucial center for the publication of Buddhist texts. His press reprinted many classical works and made them widely available, helping to revitalize Buddhist study and practice.

Wenhui, being a layperson himself, emphasized the importance of lay Buddhism. He believed that laypeople could actively engage in Buddhist practice and study without necessarily becoming monastics. This perspective was somewhat revolutionary for the time and contributed to the modernization of Buddhist practices in China. He maintained connections with Japanese Buddhist scholars and institutions. These ties facilitated the exchange of ideas and texts, further enriching the Buddhist revival in China.

Wenhui was a crucial figure in the modern revival and reform of Chinese Buddhism, emphasizing the role of laypeople, promoting the printing and dissemination of Buddhist texts, and fostering connections with international Buddhist communities. His efforts to revive Buddhism in the modern age have left a lasting impact on Chinese Buddhism. The scholars and institutions influenced by him played a significant role in shaping the trajectory of 20th-century Chinese Buddhism.

Samuel Pollard (1864-1915)

Religion and Branch: Christianity (Methodist)

Title: Missionary

Samuel Pollard was a British Methodist missionary who is particularly remembered for his work among the Miao (Hmong) people in the Yunnan province of southwest China. Arriving in China during the late 19th century, he was associated with the China Inland Mission before moving to the British and Foreign Bible Society and then the Methodist Church.

Among his most notable achievements was the development of the Pollard script, a written form of the A-Hmao (a branch of the Miao) language. By providing a script, he facilitated the translation and reading of the Bible in the native language of the Miao people, which had a significant impact on the spread of Christianity in the region.

Beyond evangelism, Pollard also emphasized education and social upliftment. He established schools and engaged in various community development projects, seeking to improve the general well-being of the Miao people. Like many missionaries in China during this period, Pollard faced challenges, including resistance to foreign religious influence and the broader political upheavals taking place in China at the time.

Pollard's work had a lasting impact on the Miao community. Many Miao embraced Christianity, and the church continued to grow even after his death. The Pollard script, though modified, is still in use among some Miao groups.

Pollard played a significant role in the spread of Christianity among the Miao people in Yunnan, China. His lasting contributions, especially the development of the Pollard script, facilitated religious, educational, and socio-cultural transformations in the region.

Copyright © 1993—2025 World Trade Press. All rights reserved.

China

China